Drag a sketch file here or click here to upload

Drop sketch file here

Draw By Numeral is a programming environment and language designed to introduce the basic concepts of computer programming by giving immediate feedback through a simple graphics rendering context.

The DBN environment presents a code editor and graphical output side-by-side in a single window. The features of the environment are described below.

Saving DBN Images: Holding down your keyboard's option key while hovering the mouse pointer over the output pane turns the cursor into a camera icon. Click to save the current image as a PNG file.

Explaining Pixels: Holding down the shift key while hovering the mouse pointer over the output pane highlights the line of code that produced the pixel under the mouse position.

The DBN language is designed to be easy for beginners. The language intentonally leaves out many features that are common in general-purpouse languages such as Python or JavaScript. By limiting the features of DBN, we can spend less time learning the complexities of a general-purpose language and more time learning broader concepts of computer programming.

A DBN program's output is a virtual sheet of paper. The paper is divided into a grid of 101 × 101 squares, each of which can be filled with a shade of gray. This document describes the basic concepts of the DBN language, which you can use to construct any number of programs that are capable of producing a vast universe of images.

The simplest DBN program consists of a single statement:

|

Paper 0 |

This statement tells DBN to color the entire paper white. Taking a closer look at the

statement, we see it consists of a command name (Paper), followed by a space,

and then a number that tells DBN how light or dark the paper should be. We call this

numerical value an argument.

Grayscale values in DBN are represented as numbers from 0 (white) to 100 (black).

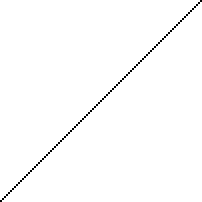

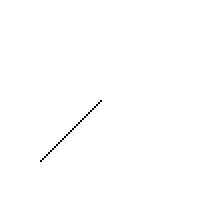

Let's look at a more complex example. The following DBN program draws a single line from the lower left to the upper right of the paper.

|

Paper 0 Pen 100 Line 0 0 100 100 |

This program consists of three statements, each on its own line. In DBN, only one statement may be written per line, and statements cannot span multiple lines.

Looking at the second line, we see a new command, Pen, which takes one

argument. Like the Paper command, the argument represents the desired grayscale

value. The Line command expects four arguments, which must be separated by

spaces.

The arguments to the Line command tell it the x and y coordinates of the two

points that will be connected by a line. In this example, the program draws a line from

A variable is a placeholder for a numeric value. Anywhere a number is used, a variable may be used in its place.

We can give the variable a value using the Set command.

Set expects two arguments: the first argument is the name we will use to refer

to the variable and the second argument is the value that will be assigned to the variable.

Set X 50

In the previvous statement, the variable called X gets the value 50. We can

refer to X elsewhere in our program by its name, as in the following

Line command:

Line 20 X 80 X

Since the variable X was previously given the value 50, the program will draw a

line from

Sometimes it's helpful to relate multiple values together into a single number. A calculation tells the computer to perform arithmetic on a sequence of numbers and variables.

Two of the symbols we use for calculation will be familiar from mathematics lessons in

school: + and - signify addition and subtraction. Instead of

× and ÷, however, we use * and / to signify

multiplication and division because we have keys for them on our keyboards.

A calculation must be wrapped in parentheses to signal to DBN where the expression begins and ends. The statement in the following example calculates the value 100−50 and sets the paper to the resulting value:

Paper (100 - 50)

Parentheses may also be used to force a different order of operations. DBN will compute

multiplication and division before addition and subtraction (just like how we learned to do

arithmetic in school). If we want to perform addition before multiplication, just enclose

the addition in parentheses like this: ((10 + 1) * 50).

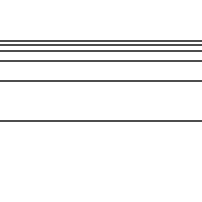

Loops are a way to perform a sequence of statements repeatedly. We could perform a command multiple times by typing it in repeatedly, but as you can see in the following example, it quickly becomes tedious to type.

|

Paper 0 Pen 70 Line 0 40 100 40 Line 0 60 100 60 Line 0 70 100 70 Line 0 75 100 75 Line 0 78 100 78 Line 0 80 100 80 |

To make it easier to perform repetition in your programs, DBN provides commands to repeat a

sequence of statements multiple times. Repeat is one such command.

A Repeat statement expects a variable name that will hold the current iteration

count, a value from which to start counting, and a value to count until. The

Repeat statement must be followed by a sequence of statements enclosed in

braces (called a block.)

Inside the block, we can refer to the variable and use it as a value to the repeated statements. This lets us repeat ourselves while changing what we say slightly each time

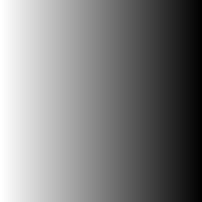

|

Paper 0

Repeat X 0 100

{

Pen X

Line X 0 X 100

}

|

In the preceding example, the Repeat statement begins by giving

X the value 0. It then executes the statements in the block and increments the

value of X by one before repeating. Once the value of X exceeds

100, the repetition stops and execution continues with the rest of the program.

Loops don't always have to count up! If the Repeat statement's end value is

less than the start value, the iteration count will decrement by 1 after

each execution of the loop body.

Occasionally we would like to be able to run a sequence of statements only when certain conditions are true. DBN provides four comparison commands that test whether the two provided values have a particular relation, and execute the block directly below them only when the desired relation holds.

Consider this program:

|

Paper 0

Pen 100

Set A 20

Smaller? A 50

{

Line A A 50 50

}

|

The Smaller? command tests whether the first argument is less than the second,

and since the value in the variable A is less than 50, the test passes and the

program executes the block with the Line

command. If we were to edit the program so the value of

A were 80, the test would fail and no line would be drawn.

The three other comparison commands are NotSmaller?, which tests whether the

first argument is larger than or the same as the second argument; Same? which

tests whether the two arguments are equal; and NotSame?, which tests whether

the two arguments are different.

Comparisons are frequently helpful when writing loops. If we want to execute certain commands only when the iteration count is within a desired range, we can use a comparison statement inside the loop body

|

Repeat X 0 100

{

Pen X

Smaller? X 50

{

Line 0 X 100 X

}

}

|

As we repeat from 0 to 100, we test the value of X each time through the loop,

and only draw a line if X is less than 50.

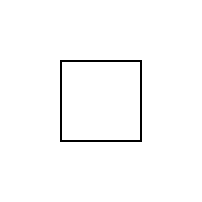

We can define our own commands with the Command command.

|

Paper 0

Pen 100

Command Rectangle x0 y0 x1 y1

{

Line x0 y0 x1 y0

Line x0 y0 x0 y1

Line x0 y1 x1 y1

Line x1 y0 x1 y1

}

Rectangle 30 30 70 70

|